How To Repair A Table Leaf Pin And Pinhole That Do Not Fit

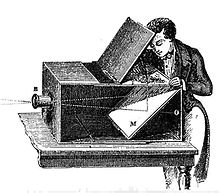

Analogy of the camera obscura principle from James Ayscough's A brusk account of the eye and nature of vision (1755 fourth edition)

An prototype of the New Royal Palace at Prague Castle projected onto an attic wall past a hole in the tile roofing

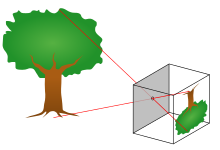

A camera obscura (plural camerae obscurae or camera obscuras, from Latin camera obscūra , "dark bedroom")[1] is a darkened room with a pocket-sized hole or lens at ane side through which an image is projected onto a wall[ii] [3] or table[4] opposite the hole.[ii] [3]

"Camera obscura" can too refer to analogous constructions such every bit a box or tent in which an exterior image is projected inside. Camera obscuras with a lens in the opening take been used since the second half of the 16th century and became popular equally aids for cartoon and painting. The concept was adult further into the photographic photographic camera in the starting time half of the 19th century, when photographic camera obscura boxes were used to betrayal calorie-free-sensitive materials to the projected image.

The photographic camera obscura was used to written report eclipses without the hazard of damaging the eyes by looking straight into the lord's day. Every bit a drawing help, information technology allowed tracing the projected image to produce a highly accurate representation, and was peculiarly appreciated as an easy manner to achieve proper graphical perspective.

Before the term photographic camera obscura was first used in 1604, other terms were used to refer to the devices: cubiculum obscurum, cubiculum tenebricosum, conclave obscurum, and locus obscurus.[v]

A camera obscura without a lens merely with a very pocket-size pigsty is sometimes referred to every bit a pinhole camera, although this more often refers to elementary (homemade) lensless cameras where photographic film or photographic paper is used.

Physical explanation [edit]

Rays of light travel in direct lines and change when they are reflected and partly absorbed past an object, retaining information most the color and brightness of the surface of that object. Lighted objects reflect rays of light in all directions. A small plenty opening in a barrier admits merely the rays that travel directly from unlike points in the scene on the other side, and these rays course an image of that scene where they reach a surface opposite from the opening.[6]

The human eye (and those of animals such as birds, fish, reptiles etc.) works much similar a camera obscura with an opening (student), a convex lens, and a surface where the image is formed (retina). Some camera obscuras apply a concave mirror for a focusing effect similar to a convex lens.[6]

Engineering [edit]

A camera obscura box with mirror, with an upright projected prototype at the height

A camera obscura consists of a box, tent, or room with a small hole in 1 side or the height. Light from an external scene passes through the pigsty and strikes a surface inside, where the scene is reproduced, inverted (upside-down) and reversed (left to right), but with color and perspective preserved.[7]

To produce a reasonably clear projected epitome, the aperture is typically smaller than ane/100th the distance to the screen. As the pinhole is made smaller, the prototype gets sharper, but dimmer. With a too small pinhole, even so, the sharpness worsens, due to diffraction. Optimum sharpness is attained with an aperture diameter approximately equal to the geometric mean of the wavelength of light and the distance to the screen.[eight]

In exercise, camera obscuras employ a lens rather than a pinhole because information technology allows a larger aperture, giving a usable effulgence while maintaining focus.[half-dozen]

If the image is caught on a translucent screen, it tin can be viewed from the back so that it is no longer reversed (but withal upside-down). Using mirrors, information technology is possible to project a right-side-upward image. The projection tin also be displayed on a horizontal surface (due east.g., a tabular array). The 18th-century overhead version in tents used mirrors inside a kind of periscope on the top of the tent.[6]

The box-type photographic camera obscura often has an angled mirror projecting an upright image onto tracing paper placed on its glass top. Although the image is viewed from the back, information technology is reversed past the mirror.[9]

History [edit]

Prehistory to 500 BCE: Possible inspiration for prehistoric fine art and possible utilize in religious ceremonies, gnomons [edit]

There are theories that occurrences of camera obscura effects (through tiny holes in tents or in screens of animal hide) inspired paleolithic cave paintings. Distortions in the shapes of animals in many paleolithic cave artworks might be inspired by distortions seen when the surface on which an epitome was projected was non direct or not in the correct angle.[10] It is also suggested that camera obscura projections could accept played a role in Neolithic structures.[11] [12]

The gnomon project on the floor of Florence Cathedral during the solstice on 21 June 2022

Perforated gnomons projecting a pinhole epitome of the sun were described in the Chinese Zhoubi Suanjing writings (1046 BCE–256 BCE with cloth added until circa 220 CE).[13] The location of the bright circumvolve tin can exist measured to tell the time of day and twelvemonth. In Arab and European cultures its invention was much later attributed to Egyptian astronomer and mathematician Ibn Yunus effectually 1000 CE.[fourteen]

500 BCE to 500 CE: Earliest written observations [edit]

Holes in the leaf awning project images of a solar eclipse on the ground.

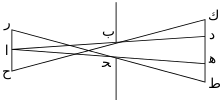

One of the earliest known written records of a pinhole photographic camera for camera obscura event is found in the Chinese text called Mozi, dated to the quaternary century BCE, traditionally ascribed to and named for Mozi (circa 470 BCE-circa 391 BCE), a Chinese philosopher and the founder of Mohist School of Logic.[15] These writings explain how the image in a "collecting-indicate" or "treasure house"[note 1] is inverted by an intersecting point (pinhole) that collects the (rays of) light. Light coming from the foot of an illuminated person were partly hidden below (i.e., strike below the pinhole) and partly formed the tiptop of the image. Rays from the head were partly hidden in a higher place (i.east., strike to a higher place the pinhole) and partly formed the lower part of the image.[16] [17]

Another early on account is provided by Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BCE), or possibly a follower of his ideas. Like to the afterwards 11th-century Arab scientist Alhazen, Aristotle is as well idea to have used photographic camera obscura for observing solar eclipses.[15] Camera obscura is touched upon every bit a bailiwick in Aristotle's work Bug – Book XV, request:

Why is information technology that when the lord's day passes through quadri-laterals, as for instance in wickerwork, it does not produce a figure rectangular in shape just circular?

and further on:

"Why is it that an eclipse of the sunday, if one looks at it through a sieve or through leaves, such as a plane-tree or other broadleaved tree, or if 1 joins the fingers of i hand over the fingers of the other, the rays are crescent-shaped where they achieve the earth? Is it for the same reason as that when calorie-free shines through a rectangular peep-hole, it appears circular in the form of a cone?"

Many philosophers and scientists of the Western world pondered this question before it was accepted that the circular and crescent-shapes described in the "problem" were pinhole image projections of the dominicus. Although a projected image has the shape of the discontinuity when the lite source, aperture and project plane are close together, the projected image has the shape of the light source when they are farther apart.

In his book Optics (circa 300 BCE, surviving in after manuscripts from effectually 1000 CE), Euclid proposed mathematical descriptions of vision with "lines drawn directly from the heart laissez passer through a infinite of swell extent" and "the grade of the space included in our vision is a cone, with its apex in the eye and its base at the limits of our vision."[eighteen] Later versions of the text, similar Ignazio Danti'south 1573 annotated translation, would add a clarification of the camera obscura principle to demonstrate Euclid's ideas.[19]

500 to 1000: Primeval experiments, report of calorie-free [edit]

Anthemius of Tralles'southward diagram of lite-rays reflected with plane mirror through hole (B)

In the 6th century, the Byzantine-Greek mathematician and architect Anthemius of Tralles (most famous as a co-architect of the Hagia Sophia) experimented with effects related to the camera obscura.[xx] Anthemius had a sophisticated understanding of the involved optics, equally demonstrated by a light-ray diagram he constructed in 555 CE.[21]

In the tenth century Yu Chao-Lung supposedly projected images of pagoda models through a small hole onto a screen to study directions and divergence of rays of light.[22]

thousand to 1400: Optical and astronomical tool, entertainment [edit]

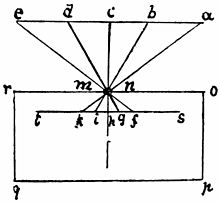

A diagram depicting Ibn al-Haytham's observations of calorie-free'due south behaviour through a pinhole

Pinhole camera. Lite enters a night box through a small-scale pigsty and creates an inverted image on the wall opposite the pigsty.[23]

Arab physicist Ibn al-Haytham (known in the West by the Latinised Alhazen) (965–1040) extensively studied the camera obscura phenomenon in the early 11th century.

In his treatise "On the shape of the eclipse" he provided the offset experimental and mathematical analysis of the miracle.[24] [25] He must have understood the relationship between the focal bespeak and the pinhole.[26]

In his Volume of Optics (circa 1027), Ibn al-Haytham explained that rays of calorie-free travel in straight lines and are distinguished by the torso that reflected the rays, writing:[27]

Evidence that light and color practice not mingle in air or (other) transparent bodies is (plant in) the fact that, when several candles are at various singled-out locations in the same area, and when they all face a window that opens into a dark recess, and when there is a white wall or (other white) opaque body in the dark recess facing that window, the (individual) lights of those candles appear individually upon that trunk or wall according to the number of those candles; and each of those lights (spots of light) appears directly contrary 1 (particular) candle forth a straight line passing through that window. Moreover, if one candle is shielded, only the light contrary that candle is extinguished, only if the shielding object is lifted, the light volition return.

He described a "night sleeping accommodation", and experimented with calorie-free passing through pocket-size pinholes, using iii side by side candles and seeing the effects on the wall after placing a cutout betwixt the candles and the wall.[28] [1]

The image of the dominicus at the fourth dimension of the eclipse, unless it is total, demonstrates that when its light passes through a narrow, round hole and is cast on a plane opposite to the hole it takes on the form of a moon-sickle. The image of the lord's day shows this peculiarity just when the hole is very small. When the hole is enlarged, the picture changes, and the change increases with the added width. When the aperture is very wide, the sickle-form image will disappear, and the light will appear round when the hole is circular, square if the pigsty is square, and if the shape of the opening is irregular, the lite on the wall will take on this shape, provided that the hole is broad and the aeroplane on which it is thrown is parallel to it.

Ibn al-Haytham also analyzed the rays of sunlight and ended that they fabricated a conic shape where they met at the hole, forming another conic shape reverse to the first one from the hole to the opposite wall in the dark room. Latin translations of his writings on eyes were very influential in Europe from about 1200 onward. Among those he inspired were Witelo, John Peckham, Roger Bacon, Leonardo da Vinci, René Descartes and Johannes Kepler.[29]

In his 1088 volume, Dream Pool Essays, the Song Dynasty Chinese scientist Shen Kuo (1031–1095) compared the focal point of a concave burning-mirror and the "collecting" hole of camera obscura phenomena to an oar in a rowlock to explain how the images were inverted:[30]

"When a bird flies in the air, its shadow moves along the ground in the aforementioned direction. But if its image is collected (shu)(like a belt being tightened) through a small hole in a window, and then the shadow moves in the direction reverse of that of the bird.[...] This is the same principle as the burning-mirror. Such a mirror has a concave surface, and reflects a finger to give an upright image if the object is very near, but if the finger moves farther and farther away it reaches a indicate where the image disappears and later on that the paradigm appears inverted. Thus the point where the image disappears is like the pinhole of the window. So also the oar is fixed at the rowlock somewhere at its middle part, constituting, when information technology is moved, a sort of 'waist' and the handle of the oar is always in the position inverse to the end (which is in the water)."

Shen Kuo too responded to a statement of Duan Chengshi in Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang written in almost 840 that the inverted image of a Chinese pagoda tower beside a seashore, was inverted because it was reflected by the sea: "This is nonsense. It is a normal principle that the prototype is inverted later passing through the small hole."[15]

English language statesman and scholastic philosopher Robert Grosseteste (c. 1175 – 9 October 1253) was i of the primeval Europeans who commented on the camera obscura.[31]

Iii-tiered camera obscura, 13th century, attributed to Roger Salary

English philosopher and Franciscan friar Roger Bacon (c. 1219/20 – c. 1292) falsely stated in his De Multiplicatione Specerium (1267) that an image projected through a foursquare aperture was round considering light would travel in spherical waves and therefore assumed its natural shape after passing through a hole. He is also credited with a manuscript that brash to study solar eclipses safely by observing the rays passing through some round hole and studying the spot of calorie-free they form on a surface.[32]

A picture of a 3-tiered camera obscura (see analogy) has been attributed to Bacon,[33] only the source for this attribution is non given. A very like picture is establish in Athanasius Kircher's Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae (1646).[34]

Smoothen friar, theologian, physicist, mathematician and natural philosopher Erazmus Ciołek Witelo (also known every bit Vitello Thuringopolonis and by many unlike spellings of the name "Witelo") wrote about the camera obscura in his very influential treatise Perspectiva (circa 1270–1278), which was largely based on Ibn al-Haytham'southward piece of work.

English archbishop and scholar John Peckham (circa 1230 – 1292) wrote nearly the camera obscura in his Tractatus de Perspectiva (circa 1269–1277) and Perspectiva communis (circa 1277–79), falsely arguing that light gradually forms the circular shape afterwards passing through the aperture.[35] His writings were influenced by Roger Salary.

At the cease of the 13th century, Arnaldus de Villa Nova is credited with using a photographic camera obscura to project live performances for amusement.[36] [37]

French astronomer Guillaume de Saint-Cloud suggested in his 1292 piece of work Almanach Planetarum that the eccentricity of the lord's day could exist determined with the photographic camera obscura from the inverse proportion between the distances and the apparent solar diameters at apogee and perigee.[38]

Kamāl al-Dīn al-Fārisī (1267–1319) described in his 1309 piece of work Kitab Tanqih al-Manazir (The Revision of the Optics) how he experimented with a glass sphere filled with water in a camera obscura with a controlled aperture and plant that the colors of the rainbow are phenomena of the decomposition of light.[39] [40]

French Jewish philosopher, mathematician, physicist and astronomer/astrologer Levi ben Gershon (1288–1344) (also known as Gersonides or Leo de Balneolis) made several astronomical observations using a photographic camera obscura with a Jacob's staff, describing methods to measure the angular diameters of the sun, the moon and the bright planets Venus and Jupiter. He determined the eccentricity of the sun based on his observations of the summertime and winter solstices in 1334. Levi also noted how the size of the aperture determined the size of the projected image. He wrote about his findings in Hebrew in his treatise Sefer Milhamot Ha-Shem (The Wars of the Lord) Book 5 Chapters v and 9.[41]

1450 to 1600: Depiction, lenses, drawing aid, mirrors [edit]

Da Vinci: Let a b c d due east be the object illuminated by the sun and o r the front end of the nighttime sleeping room in which is the said pigsty at n m. Let s t be the canvas of paper intercepting the rays of the images of these objects upside down, considering the rays being straight, a on the correct paw becomes k on the left, and e on the left becomes f on the correct[42]

Italian polymath Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), familiar with the piece of work of Alhazen in Latin translation,[43] and after an extensive study of eyes and human vision, wrote the oldest known clear description of the photographic camera obscura in mirror writing in a notebook in 1502, later published in the drove Codex Atlanticus (translated from Latin):

If the facade of a building, or a place, or a landscape is illuminated past the sun and a small pigsty is drilled in the wall of a room in a building facing this, which is not straight lighted by the sun, then all objects illuminated by the sun volition send their images through this aperture and will appear, upside downwards, on the wall facing the hole. Yous volition catch these pictures on a slice of white paper, which placed vertically in the room not far from that opening, and y'all volition see all the above-mentioned objects on this newspaper in their natural shapes or colors, only they will appear smaller and upside down, on business relationship of crossing of the rays at that discontinuity. If these pictures originate from a place which is illuminated by the dominicus, they will appear colored on the paper exactly as they are. The paper should be very thin and must be viewed from the back.[44]

These descriptions, nonetheless, would remain unknown until Venturi deciphered and published them in 1797.[45]

Da Vinci was clearly very interested in the camera obscura: over the years he drew circa 270 diagrams of the photographic camera obscura in his notebooks . He systematically experimented with various shapes and sizes of apertures and with multiple apertures (1, 2, iii, 4, viii, sixteen, 24, 28 and 32). He compared the working of the eye to that of the camera obscura and seemed specially interested in its capability of demonstrating basic principles of optics: the inversion of images through the pinhole or pupil, the non-interference of images and the fact that images are "all in all and all in every part".[46]

First published picture of camera obscura in Gemma Frisius' 1545 book De Radio Astronomica et Geometrica

The oldest known published drawing of a photographic camera obscura is constitute in Dutch physician, mathematician and instrument maker Gemma Frisius' 1545 volume De Radio Astronomica et Geometrica, in which he described and illustrated how he used the camera obscura to report the solar eclipse of 24 January 1544[45]

Italian polymath Gerolamo Cardano described using a glass disc – probably a arched lens – in a camera obscura in his 1550 book De subtilitate, vol. I, Libri IV. He suggested to use it to view "what takes place in the street when the sun shines" and advised to use a very white sheet of paper every bit a projection screen so the colours wouldn't exist dull.[47]

Sicilian mathematician and astronomer Francesco Maurolico (1494–1575) answered Aristotle's problem how sunlight that shines through rectangular holes can form circular spots of light or crescent-shaped spots during an eclipse in his treatise Photismi de lumine et umbra (1521–1554). However this wasn't published earlier 1611,[48] after Johannes Kepler had published similar findings of his ain.

Italian polymath Giambattista della Porta described the photographic camera obscura, which he called "obscurum cubiculum", in the 1558 first edition of his book series Magia Naturalis. He suggested to use a convex lens to projection the image onto paper and to use this every bit a drawing aid. Della Porta compared the man heart to the camera obscura: "For the paradigm is let into the centre through the eyeball just as here through the window". The popularity of Della Porta'due south books helped spread knowledge of the camera obscura.[49] [50]

In his 1567 work La Pratica della Perspettiva Venetian nobleman Daniele Barbaro (1513-1570) described using a camera obscura with a biconvex lens as a cartoon aid and points out that the pic is more bright if the lens is covered equally much equally to exit a circumference in the center.[47]

Illustration of "portable" photographic camera obscura (similar to Risner's proposal) in Kircher's Ars Magna Lucis Et Umbrae (1645)

In his influential and meticulously annotated Latin edition of the works of Ibn al-Haytham and Witelo, Opticae thesauru (1572), German language mathematician Friedrich Risner proposed a portable photographic camera obscura drawing aid; a lightweight wooden hut with lenses in each of its four walls that would project images of the surroundings on a paper cube in the middle. The construction could be carried on two wooden poles.[51] A very similar setup was illustrated in 1645 in Athanasius Kircher's influential book Ars Magna Lucis Et Umbrae.[52]

Around 1575 Italian Dominican priest, mathematician, astronomer, and cosmographer Ignazio Danti designed a camera obscura gnomon and a meridian line for the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, Florence and he later had a massive gnomon built in the San Petronio Basilica in Bologna. The gnomon was used to written report the movements of the sunday during the year and helped in determining the new Gregorian calendar for which Danti took identify in the commission appointed past Pope Gregorius Xiii and instituted in 1582.[53]

In his 1585 book Diversarum Speculationum Mathematicarum [54] Venetian mathematician Giambattista Benedetti proposed to use a mirror in a 45-caste angle to projection the image upright. This leaves the image reversed, only would get mutual practice in later camera obscura boxes.[47]

Giambattista della Porta added a "lenticular crystal" or biconvex lens to the camera obscura description in the 1589 2nd edition of Magia Naturalis. He besides described use of the camera obscura to project hunting scenes, banquets, battles, plays, or anything desired on white sheets. Trees, forests, rivers, mountains "that are really so, or fabricated past Art, of Forest, or another affair" could be bundled on a plainly in the sunshine on the other side of the camera obscura wall. Lilliputian children and animals (for case handmade deer, wild boars, rhinos, elephants, and lions) could perform in this gear up. "Then, by degrees, they must appear, every bit coming out of their dens, upon the Plainly: The Hunter he must come with his hunting Pole, Nets, Arrows, and other necessaries, that may represent hunting: Permit there be Horns, Cornets, Trumpets sounded: those that are in the Chamber shall see Trees, Animals, Hunters Faces, and all the rest so plainly, that they cannot tell whether they be truthful or delusions: Swords drawn will glister in at the pigsty, that they will brand people near afraid." Della Porta claimed to have shown such spectacles often to his friends. They admired it very much and could hardly be convinced by Della Porta's explanations that what they had seen was really an optical play tricks.[49] [55] [56]

1600 to 1650: Proper name coined, camera obscura telescopy, portable drawing aid in tents and boxes [edit]

The first utilize of the term "photographic camera obscura" was by Johannes Kepler, in his starting time treatise about optics, Ad Vitellionem paralipomena quibus astronomiae pars optica traditur (1604)[57]

Item of Scheiner's Oculus hoc est (1619) frontispiece with a camera obscura'due south projected image reverted by a lens

The earliest use of the term "camera obscura" is establish in the 1604 book Ad Vitellionem Paralipomena by German mathematician, astronomer, and astrologer Johannes Kepler.[57] Kepler discovered the working of the photographic camera obscura by recreating its principle with a book replacing a shining trunk and sending threads from its edges through a many-cornered aperture in a table onto the floor where the threads recreated the shape of the volume. He as well realized that images are "painted" inverted and reversed on the retina of the centre and figured that this is somehow corrected by the brain.[58] In 1607, Kepler studied the sun in his camera obscura and noticed a sunspot, just he thought it was Mercury transiting the lord's day.[59] In his 1611 volume Dioptrice, Kepler described how the projected prototype of the camera obscura can be improved and reverted with a lens. It is believed he later used a telescope with three lenses to revert the image in the camera obscura.[47]

In 1611, Frisian/High german astronomers David and Johannes Fabricius (father and son) studied sunspots with a photographic camera obscura, after realizing looking at the sun directly with the telescope could damage their eyes.[59] They are thought to have combined the telescope and the camera obscura into camera obscura telescopy.[59] [60]

In 1612, Italian mathematician Benedetto Castelli wrote to his mentor, the Italian astronomer, physicist, engineer, philosopher, and mathematician Galileo Galilei virtually projecting images of the dominicus through a telescope (invented in 1608) to report the recently discovered sunspots. Galilei wrote virtually Castelli's technique to the German Jesuit priest, physicist, and astronomer Christoph Scheiner.[61]

Scheiner's helioscope equally illustrated in his book Rosa Ursina sive Sol (1626–30)

From 1612 to at to the lowest degree 1630, Christoph Scheiner would keep on studying sunspots and constructing new telescopic solar-projection systems. He called these "Heliotropii Telioscopici", later on contracted to helioscope.[61] For his helioscope studies, Scheiner congenital a box around the viewing/projecting end of the telescope, which can be seen as the oldest known version of a box-blazon camera obscura. Scheiner also fabricated a portable camera obscura.[62]

In his 1613 book Opticorum Libri Sex [63] Belgian Jesuit mathematician, physicist, and builder François d'Aguilon described how some charlatans cheated people out of their money by claiming they knew necromancy and would heighten the specters of the devil from hell to prove them to the audience inside a night room. The image of an banana with a devil's mask was projected through a lens into the dark room, scaring the uneducated spectators.[32]

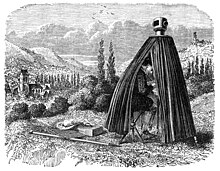

A camera obscura drawing aid tent in an analogy for an 1858 book on physics

By 1620 Kepler used a portable photographic camera obscura tent with a modified telescope to draw landscapes. It could be turned effectually to capture the surroundings in parts.[64]

Dutch inventor Cornelis Drebbel is thought to have constructed a box-type photographic camera obscura which corrected the inversion of the projected prototype. In 1622, he sold i to the Dutch poet, composer, and diplomat Constantijn Huygens who used it to paint and recommended information technology to his artist friends.[51] Huygens wrote to his parents (translated from French):

I accept at habitation Drebbel'south other instrument, which certainly makes beauteous effects in painting from reflection in a dark room; it is not possible for me to reveal the dazzler to you in words; all painting is dead by comparison, for here is life itself or something more elevated if i could articulate it. The figure and the contour and the movements come together naturally therein and in a grandly pleasing style.[65]

Illustration of a scioptic ball with a lens from Daniel Schwenter'south Deliciae Physico-Mathematicae (1636)

German Orientalist, mathematician, inventor, poet, and librarian Daniel Schwenter wrote in his 1636 book Deliciae Physico-Mathematicae about an instrument that a man from Pappenheim had shown him, which enabled movement of a lens to project more from a scene through the photographic camera obscura. It consisted of a brawl as big every bit a fist, through which a hole (AB) was made with a lens fastened on ane side (B). This brawl was placed within two-halves of role of a hollow brawl that were and then glued together (CD), in which it could be turned around. This device was attached to a wall of the camera obscura (EF).[66] This universal joint machinery was afterwards called a scioptric ball.

In his 1637 book Dioptrique French philosopher, mathematician and scientist René Descartes suggested placing an eye of a recently dead human (or if a expressionless man was unavailable, the eye of an ox) into an opening in a darkened room and scraping away the mankind at the back until one could see the inverted paradigm formed on the retina.[67]

Illustration of a twelve-hole photographic camera obscura from Bettini'southward Apiaria universae philosophiae mathematicae (1642)

Italian Jesuit philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer Mario Bettini wrote about making a camera obscura with twelve holes in his Apiaria universae philosophiae mathematicae (1642). When a foot soldier would stand up in front end of the camera, a twelve-person army of soldiers making the same movements would be projected.

French mathematician, Minim friar, and painter of anamorphic art Jean-François Nicéron (1613–1646) wrote about the photographic camera obscura with convex lenses. He explained how the camera obscura could be used past painters to achieve perfect perspective in their piece of work. He too complained how charlatans driveling the camera obscura to fool witless spectators and make them believe that the projections were magic or occult science. These writings were published in a posthumous version of La Perspective Curieuse (1652).[68]

1650 to 1800: Introduction of the magic lantern, popular portable box-type drawing aid, painting aid [edit]

The use of the camera obscura to project special shows to entertain an audience seems to have remained very rare. A description of what was most likely such a show in 1656 in France, was penned by the poet Jean Loret. The Parisian society were presented with upside-down images of palaces, ballet dancing and battling with swords. The functioning was silent and Loret was surprised that all the movements made no sound. Loret felt somewhat frustrated that he did not know the surreptitious that made this spectacle possible. There are several clues that this was a camera obscura bear witness, rather than a very early magic lantern show, specially in the upside-down image and the energetic movements.[69]

German Jesuit scientist Gaspar Schott heard from a traveler about a pocket-size camera obscura device he had seen in Spain, which ane could behave under one arm and could be hidden under a coat. He so constructed his own sliding box photographic camera obscura, which could focus by sliding a wooden box office fitted inside another wooden box part. He wrote most this in his 1657 Magia universalis naturæ et artis (volume one – book iv "Magia Optica" pages 199–201).

Past 1659 the magic lantern was introduced and partly replaced the camera obscura as a project device, while the camera obscura more often than not remained popular every bit a drawing help. The magic lantern tin be seen as a development of the (box-blazon) camera obscura device.

The 17th century Dutch Masters, such as Johannes Vermeer, were known for their magnificent attention to detail. It has been widely speculated that they made use of the camera obscura,[64] but the extent of their employ past artists at this period remains a thing of fierce contention, recently revived past the Hockney–Falco thesis.[51]

High german philosopher Johann Sturm published an illustrated commodity virtually the construction of a portable photographic camera obscura box with a 45° mirror and an oiled paper screen in the first volume of the proceedings of the Collegium Curiosum, Collegium Experimentale, sive Curiosum (1676).[70]

Johann Zahn's Oculus Artificialis Teledioptricus Sive Telescopium, published in 1685, contains many descriptions, diagrams, illustrations and sketches of both the camera obscura and the magic lantern. A paw-held device with a mirror-reflex mechanism was first proposed by Johann Zahn in 1685, a pattern that would later be used in photographic cameras.[71]

The scientist Robert Hooke presented a paper in 1694 to the Imperial Club, in which he described a portable photographic camera obscura. It was a cone-shaped box which fit onto the head and shoulders of its user.[72]

From the beginning of the 18th century, craftsmen and opticians would make camera obscura devices in the shape of books, which were much appreciated by lovers of optical devices.[32]

One chapter in the Conte Algarotti's Saggio sopra Pittura (1764) is dedicated to the utilise of a camera ottica ("optic chamber") in painting.[73]

By the 18th century, following developments past Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke, more than easily portable models in boxes became available. These were extensively used by amateur artists while on their travels, but they were also employed by professionals, including Paul Sandby and Joshua Reynolds, whose camera (disguised every bit a book) is now in the Science Museum in London. Such cameras were after adjusted by Joseph Nicephore Niepce, Louis Daguerre and William Play a joke on Talbot for creating the kickoff photographs.

Function in the modern age [edit]

While the technical principles of the photographic camera obscura take been known since artifact, the broad apply of the technical concept in producing images with a linear perspective in paintings, maps, theatre setups, and architectural, and, later on, photographic images and movies started in the Western Renaissance and the scientific revolution. Although Alhazen (Ibn al-Haytham) had already observed an optical effect and developed a pioneering theory of the refraction of light, he was less interested in producing images with information technology (compare Hans Belting 2005); the society he lived in was even hostile (compare Aniconism in Islam) toward personal images.[74]

Western artists and philosophers used the Arab findings in new frameworks of epistemic relevance.[75] For example, Leonardo da Vinci used the camera obscura as a model of the middle, René Descartes for eye and listen, and John Locke started to use the camera obscura as a metaphor of human understanding per se.[76] The modern employ of the camera obscura equally an epistemic machine had of import side effects for science.[77] [78]

While the utilise of the camera obscura has waxed and waned, one tin can still be built using a few simple items: a box, tracing paper, record, foil, a box cutter, a pencil, and a coating to keep out the light.[79] Homemade camera obscura are popular chief- and secondary-school science or fine art projects.

In 1827, critic Vergnaud complained nigh the frequent use of camera obscura in producing many of the paintings at that yr'due south Salon exhibition in Paris: "Is the public to blame, the artists, or the jury, when history paintings, already rare, are sacrificed to genre painting, and what genre at that!... that of the camera obscura."[lxxx] (translated from French)

British photographer Richard Learoyd has specialized in making pictures of his models and motifs with a photographic camera obscura instead of a modern camera, combining it with the ilfochrome process which creates large grainless prints.[81] [82]

Other contemporary visual artists who have explicitly used camera obscura in their artworks include James Turrell, Abelardo Morell, Minnie Weisz, Robert Calafiore, Vera Lutter, Marja Pirilä, and Shi Guorui.[83]

Gallery [edit]

-

A camera obscura created by Mark Ellis in the style of an Adirondack mount cabin, Lake Flower, Saranac Lake, New York

-

A modern-24-hour interval photographic camera obscura

-

Modern-day photographic camera obscura used outdoors

Large public access installations [edit]

| Name | Urban center or Boondocks | Country | Comment | Corresponding external links |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astronomy Centre | Todmorden | England | 80 inches (200 cm) table, twoscore° field of view, horizontal rotation 360°, vertical adjustment ±xv° | Equipment on site#Camera obscura |

| Sovereign Hill | Ballarat | Commonwealth of australia | Inside the historical camera demonstration room | Sovereign Hill |

| Bristol Observatory | Bristol | England | View of Clifton Suspension Span | Clifton Observatory |

| Buzza Tower | Hugh Town, Isles of Scilly | England | View of the Isles of Scilly | Scilly Photographic camera Obscura |

| Camera Obscura Whangarei | Whangarei | New Zealand | View of the Te Matau ā Pohe Bascule Bridge | Photographic camera Obscura Whangarei |

| Rufford Abbey | Nottingham | England | View of the garden and house | Rufford Abbey |

| Cheverie Photographic camera Obscura | Chéverie, Nova Scotia | Canada | View of the Bay of Fundy | Cheverie Camera Obscura |

| Photographer's Gallery | London | England | View of Ramillies St | Photographer's Gallery |

| Constitution Hill | Aberystwyth | Wales | 14-inch (356 mm) lens, which is claimed to be the largest in the world | Cliff Railway and Camera Obscura, Aberystwyth View from Aberystwyth's photographic camera obscura |

| Photographic camera Obscura, and World of Illusions | Edinburgh | Scotland | Top of Royal Mile, just beneath Edinburgh Castle. Fine views of the city | Edinburgh'due south Camera Obscura |

| Camera Obscura (Greenwich) | Greenwich | England | Regal Observatory, Meridian Courtyard | http://www.rmg.co.uk/run across-do/nosotros-recommend/attractions/camera-obscura/ |

| Museum zur Vorgeschichte des Films | Mülheim | Germany | Claimed to exist the biggest "walk-in" Camera Obscura in the world. Installed in Broich Watertower in 1992 | https://web.annal.org/web/20160921065718/http://www.camera-obscura-muelheim.de/cms/the_camera.html |

| Dumfries Museum | Dumfries | Scotland | In a converted windmill belfry. Claims to be oldest working example in the earth | [1] |

| Foredown Belfry | Portslade, Brighton | England | One of only two operational camera obscuras in the south of England | |

| Grand Union Camera Obscura | Douglas | Isle of mann | On Douglas Head. Unique Victorian tourist attraction with eleven lenses | Visit Isle of man |

| Photographic camera Obscura (Giant Camera) | Golden Gate National Recreation Area, San Francisco, California | United States | Adjacent to the Cliff House below Sutro Heights Park, with views of the Pacific Body of water. In the Sutro Celebrated Commune, and on the National Register of Historic Places. | Giant Camera |

| Santa Monica Camera Obscura | Santa Monica, California | Usa | In Palisades Park overlooking Santa Monica Beach, Santa Monica Pier, and the Pacific Bounding main. Congenital in 1898. | Atlas Obscura |

| Long Island'southward Camera Obscura | Greenport, Suffolk Canton, New York | United states | In Mitchell Park overlooking the Peconic Bay and Shelter Island, New York. Congenital in 2004. | Long Island Camera Obscura |

| Griffith Observatory | Los Angeles, California | | United States | Slowly rotates and gives a panoramic view of the Los Angeles Bowl. | Griffith Park Camera Obscura |

| The Exploratorium's Bay Observatory Terrace | San Francisco, California | Us | Offers a view of San Francisco Bay, Treasure Island, and the Bay Bridge | [2] |

| Cámara Oscura | Havana | | Cuba | Located in Plaza Vieja, Havana. Offers a view of Onetime Havana | |

| Deject Chamber for the Trees and Sky | Raleigh, North Carolina | U.s. | On the campus of the North Carolina Museum of Art | http://ncartmuseum.org/fine art/detail/cloud_chamber_for_the_trees_and_sky/ |

| Camera Obscura | Grahamstown | Due south Africa | In the Observatory Museum | http://www.sa-venues.com/things-to-do/easterncape/observatory-museum/ |

| Kirriemuir Camera Obscura | Kirriemuir | Scotland | Offers a view of Kirriemuir and the surrounding glens. | |

| Torre Tavira | Cadiz | Spain | Offers a view of the old town | https://world wide web.torretavira.com/en/visiting-the-tavira-tower/ |

| Camera Obscura, Tavira | Tavira | Portugal | Uses a repurposed water tower for the viewing room. | http://family.portugalconfidential.com/camera-obscura-in-the-belfry-of-tavira/ |

| Camera Obscura, Lisbon | Lisbon | Portugal | Installed in the Castle of Saint George, Lisbon. |

See also [edit]

- Bonnington Pavilion – the offset Scottish Camera Obscura, dating from 1708

- Blackness mirror

- Bristol Observatory

- Camera lucida

- History of picture palace

- Hockney–Falco thesis

- Optics

- Pepper's ghost

Notes [edit]

- ^ In the Mozi passage, a camera obscura is described every bit a "collecting-betoken" or "treasure house" (庫); the 18th-century scholar Bi Yuan (畢沅) suggested this was a misprint for "screen" (㢓).

References [edit]

- ^ a b "Introduction to the Camera Obscura". web log.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk. Science and Media Museum. 28 January 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ a b Keener, Katherine (two March 2022). "A Lesson on the Camera Obscura". Fine art Critique . Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ a b Keats, Jonathon. "Prior To Demolition, These LACMA Galleries Took Selfies With A Petty Aid From The Pinhole Lensman Vera Lutter". Forbes . Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ "Table photographic camera obscura, 19th century". SSPL Prints . Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ Phelps Cuff, Henry (1914). Optic projection, principles, installation, and use of the magic lantern, projection microscope, reflecting lantern, moving picture automobile. Comstock Publishing Company.

obscurum cubiculum.

- ^ a b c d Standage, H. C. (1773). "The Camera Obscura: Its Uses, Action, and Construction". Amateur work, illustrated. Vol. 4. pp. 67–71.

- ^ Melvin Lawrence DeFleur, and Sandra Ball-Rokeach (1989). Theories of Mass Communication (5 ed.). Longman. p. 65. ISBN9780801300073 . Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Heinrich F. Beyer and Viateheslav P. Shevelko (2016). Introduction to the Physics of Highly Charged Ions. CRC Press. p. 42. ISBN9781420034097 . Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Steadman, Philip (2002). Vermeer's Camera: Uncovering the Truth Behind the Masterpieces. Oxford University Press. p. 9. ISBN9780192803023 . Retrieved eleven January 2022.

- ^ "Paleolithic". paleo-camera. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ "Neolithic". paleo-camera. Retrieved two May 2022.

- ^ Jennifer Ouellette (29 June 2022). "deadspin-quote-carrot-aligned-westward-bgr-ii". Gizmodo.

- ^ Boulger, Demetrius Charles (1969). The Asiatic Review.

- ^ Rohr, René R.J. (2012). Sundials: History, Theory, and Practice. p. 6. ISBN978-0-486-15170-0.

- ^ a b c Needham, Joseph. Scientific discipline and Civilization in China, vol. Four, part 1: Physics and Physical Technology (PDF). p. 98. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2022. Retrieved five September 2022.

- ^ "Ancient Greece". paleo-camera. 9 March 2022.

- ^ Ruffles, Tom (2004). Ghost Images: Cinema of the Afterlife. pp. 15–17. ISBN9780786420056.

- ^ Optics of Euclid (PDF).

- ^ "Kleine Geschichte der Lochkamera oder Camera Obscura" (in German language).

- ^ M. Huxley (1959) Anthemius of Tralles: a study of later Greek Geometry pp. 6–8, pp.44–46 as cited in (Crombie 1990), p.205

- ^ Renner, Eric (2012). Pinhole Photography: From Historic Technique to Digital Application (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 Feb 2022. Retrieved eleven February 2022.

- ^ Hammond, John H. (1981). The camera obscura: a chronicle. p. 2. ISBN9780852744512.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, Larry D.; Francis, Gregory Eastward. (2007). "Light". Physics: A World View (6 ed.). Belmont, California: Thomson Brooks/Cole. p. 339. ISBN978-0-495-01088-3.

- ^ Raynaud, Dominique (2016). A Critical Edition of Ibn al-Haytham'south On the Shape of the Eclipse. The Offset Experimental Study of the Photographic camera Obscura. New York: Springer International.

- ^ Needham, Joseph. Scientific discipline and Civilization in Prc, vol. Four, office i: Physics and Physical Engineering science (PDF). p. 98. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

it seems that, like Shen Kua, he had predecessors in its study, since he did not claim it as whatsoever new finding of his ain. But his treatment of it was competently geometrical and quantitative for the first time.

- ^ Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilization in China, vol. 4, role 1: Physics and Physical Technology (PDF). p. 99. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2022. Retrieved v September 2022.

The genius of Shen Kua's insight into the relation of focal point and pinhole tin better be appreciated when we read in Vocalist that this was first understood in Europe by Leonardo da Vinci (+ 1452 to + 1519), almost five hundred years later. A diagram showing the relation occurs in the Codice Atlantico, Leonardo thought that the lens of the centre reversed the pinhole effect, then that the image did not appear inverted on the retina; though in fact it does. Really, the analogy of focal-point and pin-indicate must accept been understood by Ibn al-Haitham, who died merely about the time when Shen Kua was born.

- ^ A. Mark Smith, ed. & trans., "Alhacen'due south Theory of Visual Perception: A Critical Edition, with English Translation and Commentary, of the First Three Books of Alhacen's De Aspectibus, the Medieval Latin Version of Ibn Al-Haytham's Kitāb Al-Manāẓir," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 91, 4–5 (2001): i–clxxxi, 1–337, 339–819 at 379, paragraph 6.85.

- ^ User, Super. "History of Camera Obscuras – Kirriemuir Camera Obscura". www.kirriemuircameraobscura.com . Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ Plott, John C. (1984). Global History of Philosophy: The Period of scholasticism (part i). p. 460. ISBN9780895816788.

- ^ Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilization in People's republic of china, vol. Iv, part i: Physics and Concrete Technology (PDF). pp. 97–98. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (1 Jan 1970). "A afterthought of Roger Bacon's theory of pinhole images". Annal for History of Exact Sciences. half-dozen (iii): 214–223. doi:10.1007/BF00327235 – via Springer Link.

- ^ a b c Mannoni, Laurent (2000). The great art of light and shadow. p. v. ISBN9780859895675.

- ^ Doble, Rick (2012). 15 Years of Essay-Blogs About Contemporary Art & Digital Photography. ISBN9781300198550.

- ^ Kircher, Athanasius (1646). Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae.

- ^ Lindberg, David C.; Pecham, John (1972). Tractatus de perspectiva.

- ^ Burns, Paul T. "The History of the Discovery of Cinematography". Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ Smith, Roger. "A Expect into Photographic camera Obscuras". Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ Mancha, J.Fifty. (2006). Studies in Medieval Astronomy and Eyes. pp. 275–297. ISBN9780860789963.

- ^ Nader El-Bizri, "Optics", in Medieval Islamic Culture: An Encyclopedia, ed. Josef W. Meri (New York – London: Routledge, 2005), Vol. Ii, pp. 578–580

- ^ Nader El-Bizri, "Al-Farisi, Kamal al-Din," in The Biographical Encyclopaedia of Islamic Philosophy, ed. Oliver Leaman (London – New York: Thoemmes Continuum, 2006), Vol. I, pp. 131–135

- ^ Goldstein, Bernard R. (6 Dec 2022). The Astronomy of Levi ben Gerson. pp. 140–143. ISBN9789401133425.

- ^ Jean Paul Richter, ed. (1880). "The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci". FromOldBooks.org. p. 71.

- ^ Zewail, Ahmed H.; Thomas, John Meurig (2010), 4D Electron Microscopy: Imaging in Space and Time, Earth Scientific, p. 5, ISBN9781848163904 : "The Latin translation of Alhazen's work influenced scientists and philosophers such equally (Roger) Bacon and da Vinci, and formed the foundation for the piece of work by mathematicians like Kepler, Descartes and Huygens..."

- ^ Josef Maria Eder History of Photography translated past Edward Epstean Hon. F.R.P.Southward Copyright Columbia Academy Press

- ^ a b Grepstad, Jon (20 October 2022). "Pinhole Photography – History, Images, Cameras, Formulas".

- ^ "Leonardo and the Camera Obscura / Kim Veltman". Sumscorp.com. 2 December 1986. Archived from the original on 18 September 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d Ilardi, Vincent (2007). Renaissance Vision from Spectacles to Telescopes. American Philosophical Order. p. 220. ISBN9780871692597.

- ^ Maurolico, Francesco (1611). Photismi de lumine et umbra.

- ^ a b Larsen, Kenneth. "Sonnet 24". Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Durbin, P.T. (2012). Philosophy of Engineering. p. 74. ISBN9789400923034.

- ^ a b c Snyder, Laura J. (2015). Eye of the Beholder. ISBN9780393246520.

- ^ Kircher, Athanasius (1645). "Ars Magna Lucis Et Umbrae" (in Latin). p. 806b.

- ^ Cassini. "1655–2005: 350 Years of the Great Meridian Line".

- ^ Benedetti, Giambattista (1585). Diversarum Speculationum Mathematicarum (in Latin).

- ^ Giovanni Battista della Porta (1658). Natural Magick (Book XVII, Chap. V + VI). pp. 363–365.

- ^ Porta, Giovan Battista Della (1589). Magia Naturalis (in Latin).

- ^ a b Dupre, Sven (2008). "Within the "Camera Obscura": Kepler'due south Experiment and Theory of Optical Imagery". Early Scientific discipline and Medicine. 13 (3): 219–244. doi:10.1163/157338208X285026. hdl:1874/33285. JSTOR 20617729.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (1981). Theories of Vision from Al-kindi to Kepler. ISBN9780226482354.

- ^ a b c "This Month in Physics History". www.aps.org.

- ^ Surdin, V., and M. Kartashev. "Lite in a dark room." Quantum 9.half-dozen (1999): 40.

- ^ a b Whitehouse, David (2004). The Sun: A Biography. ISBN9781474601092.

- ^ Daxecker, Franz (2006). "Christoph Scheiner und die Photographic camera obscura". Bibcode:2006AcHA...28...37D.

- ^ d'Aguilon, François (1613). Opticorum Libri Sex philosophis juxta ac mathematicis utiles.

- ^ a b Steadman, Philip; Vermeer, Johannes, 1632–1675 (2001). Vermeer's camera : uncovering the truth behind the masterpieces . Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-19-280302-iii.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wheelock, Jr, Arthur K. (2013). "Constantijn huygens and early attitudes towards the camera obscura". History of Photography. ane (2): 93–103. doi:10.1080/03087298.1977.10442893.

- ^ Schwenter, Daniel (1636). Deliciae Physico-Mathematicae (in German). Endter. p. 255.

- ^ Collins, Jane; Nisbet, Andrew (2012). Theatre and Functioning Blueprint: A Reader in Scenographyy. ISBN9781136344527.

- ^ Nicéron, Jean François (1652). La Perspective curieuse (in French). Chez la veufue F. Langlois, dit Chartres.

- ^ http://www.magiclantern.org.uk/new-magic-lantern-journal/pdfs/4008787a.pdf[ bare URL PDF ]

- ^ Sturm, Johann (1676). Collegium experimentale, sive curiosum (in Latin). pp. 161–163.

- ^ Gernsheim, pp. 5–half dozen

- ^ Wenczel, pg. 15

- ^ Algarotti, Francesco (1764). Presso Marco Coltellini, Livorno (ed.). Saggio sopra la pittura . pp. 59–63.

- ^ Hans Belting Das echte Bild. Bildfragen als Glaubensfragen. München 2005, ISBN 3-406-53460-0

- ^ An Anthropological Trompe L'Oeil for a Common Earth: An Essay on the Economic system of Knowledge, Alberto Corsin Jimenez, Berghahn Books, fifteen June 2022

- ^ Philosophy of Applied science: Practical, Historical and Other Dimensions P.T. Durbin Springer Science & Business Media

- ^ Contesting Visibility: Photographic Practices on the East African Coast Heike Behrend transcript, 2022

- ^ Don Ihde Art Precedes Science: or Did the Photographic camera Obscura Invent Mod Science? In Instruments in Art and Science: On the Architectonics of Cultural Boundaries in the 17th Century Helmar Schramm, Ludger Schwarte, January Lazardzig, Walter de Gruyter, 2008

- ^ "Camera Obscura and World of Illusions Edinburgh - fun for all the family". Camera Obscura and World of Illusions Edinburgh.

- ^ Pinson, Stephen (1 July 2003). "Daguerre, expérimentateur du visuel". Études photographiques (in French) (13): 110–135. ISSN 1270-9050.

- ^ "Exuberant and tragic poppies: An interview with Richard Learoyd".

- ^ "Photography Without Negatives".

- ^ "Contemporary Photographers and the Photographic camera Obscura". I Require Art. 14 February 2022. Retrieved 17 Jan 2022.

Sources [edit]

- Crombie, Alistair Cameron (1990), Science, eyes, and music in medieval and early modern thought, Continuum International Publishing Grouping, p. 205, ISBN978-0-907628-79-eight , retrieved 22 August 2022

- Kelley, David H.; Milone, E. F.; Aveni, A. F. (2005), Exploring Ancient Skies: An Encyclopedic Survey of Archaeoastronomy, Birkhäuser, ISBN978-0-387-95310-6, OCLC 213887290

- Hill, Donald R. (1993), "Islamic Science and Applied science", Edinburgh University Printing, folio 70.

- Lindberg, D.C. (1976), "Theories of Vision from Al Kindi to Kepler", The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London.

- Nazeef, Mustapha (1940), "Ibn Al-Haitham As a Naturalist Scientist", (in Standard arabic), published proceedings of the Memorial Gathering of Al-Hacan Ibn Al-Haitham, 21 Dec 1939, Egypt Press.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in Red china: Volume 4, Physics and Concrete Engineering, Office 1, Physics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Omar, S.B. (1977). "Ibn al-Haitham's Optics", Bibliotheca Islamica, Chicago.

- Raynaud, D. (2016), A Critical Edition of Ibn al-Haytham'due south On the Shape of the Eclipse. The Offset Experimental Study of the Photographic camera Obscura, New York: Springer International, ISBN9783319479910

- Wade, Nicholas J.; Finger, Stanley (2001), "The eye as an optical instrument: from camera obscura to Helmholtz's perspective", Perception, 30 (10): 1157–1177, doi:ten.1068/p3210, PMID 11721819, S2CID 8185797

- Lefèvre, Wolfgang (ed.) Within the Photographic camera Obscura: Optics and Art nether the Spell of the Projected Image. Max Planck Institut Fur Wissenschaftgesichte. Max Planck Institituter for the History of Science [3]

- Burkhard Walther, Przemek Zajfert: Camera Obscura Heidelberg. Black-and-white photography and texts. Historical and gimmicky literature. edition merid, Stuttgart, 2006, ISBN 3-9810820-0-ane

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Camera obscura at Wikimedia Eatables

Media related to Camera obscura at Wikimedia Eatables

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camera_obscura

Posted by: reavestharrife.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Repair A Table Leaf Pin And Pinhole That Do Not Fit"

Post a Comment